I had seen three of the same photo of Bill Clinton before I got into the main room of the Reduta Jazz Club. It’s all dark wood and velvet, down the stairs, cloakroom, dingy bar down to the right. I grabbed a glass of orange juice (45 CZK or $1.87) in a moment of panic and sat at a table for one lit by a fake flickering candle.

I had been dreading a visit to Reduta for a month. The club is most famous for Bill Clinton’s performance of Summertime on stage there during a visit in 1997. By then it had been established as one of the best venues in Europe and hosted the biggest names in American and Czech jazz each week. The club opened in 1958 and continued to host musicians through the most repressive years of the 20th century.

Something happened, though. The following is the lineup for this week, August 2022:

8/1: Tribute to World Legends: Ray Charles

8/2: The Best Jazz from New Orleans: JJ Jazzmen

8/3: The Best of Reduta: Louis Armstrong, Gershwin, Jobim

8/4: Tribute to World Legends: Billie Holliday

8/5: Tribute to World Legends: Frank Sinatra

8/6: Tribute to World Legends: Nina Simone

8/7: Best of Vintage Jazz and Blues: Louis Armstrong, Bessie Smith, Billie Holliday

What was once the cutting edge of European jazz now boasts a program of tribute acts every night of the week. I sucked it up and bought a ticket for the Ella Fitzgerald set on my last night in Prague.

I decided that, for the first time in my life, I would suspend judgment. Maybe tribute acts are Prague’s spot for breakout talent. Or maybe the Israeli man would show up again and we’d get to chatting and he’d offer me his extra ticket to a Metallica concert in Amsterdam during my layover and I’d go and love it so much that we both decide to build our lives together in Amsterdam and I renounce my American citizenship like Tina Turner.

A few days before, I met my pal Emil for dinner, an elder statesman of the Prague jazz scene. Wikipedia calls him the “father of Czech jazz piano.” I call him “my target demographic.” I asked him about Reduta as he slurped tomato soup in 4pm heat outside the Italian restaurant under his apartment. How had the club gone from Wynton Marsalis to tribute lounge acts in less than a decade?

He told me the shift has happened even more recently, when the club came under new management around 2018. Now, the program is the same every week, and there’s no longer any room for the old Czech masters or well-known touring acts. Emil had a simple explanation: the new management is Russian.

“I saw them roll their tanks through here in 1968,” he told me. “I’ll never trust any of them again.” Reduta’s change was a real tragedy for him. Emil had played the club since the 60’s, and he met his idols there. But he won’t go back now.

Emil doesn’t try to hide his anti-Russian prejudice. Evidence of the damage wrought on this country, he says, is all around the city. What he chalks up to the new guys at Reduta, though, is more complicated, involving the myth of music and freedom during the Cold War and the commandeered legacy of folks like Vaclav Havel. But that’s all for my thesis, which is available only to paying subscribers.

To be clear, the musicians were good, and the singer knew Ella’s improvisations note for note. And for a set that plays nearly every week, the band seemed to be enjoying themselves. I never want to ridicule the honest work of anyone (except for my friends and family and people who deserve it). I was angrier at the programming itself, and the posturing. A storied establishment, celebrating the greats, but clinging to the fading glory of its own past while making no effort for the present. The club is run like a Paula Deen restaurant.

To be clear again, the music was also annoying. It was almost, though not quite, like that most offensive of Spotify playlists: Jazz in the Background. This stuff runs the joy and surprise of music through a fine mesh sieve until the most inane kitten-breath-electric-hand-dryer-softness trickles out. This music feels like when someone touches you lightly on the small of your back to squeeze by you in a crowded room—infuriatingly gentle.

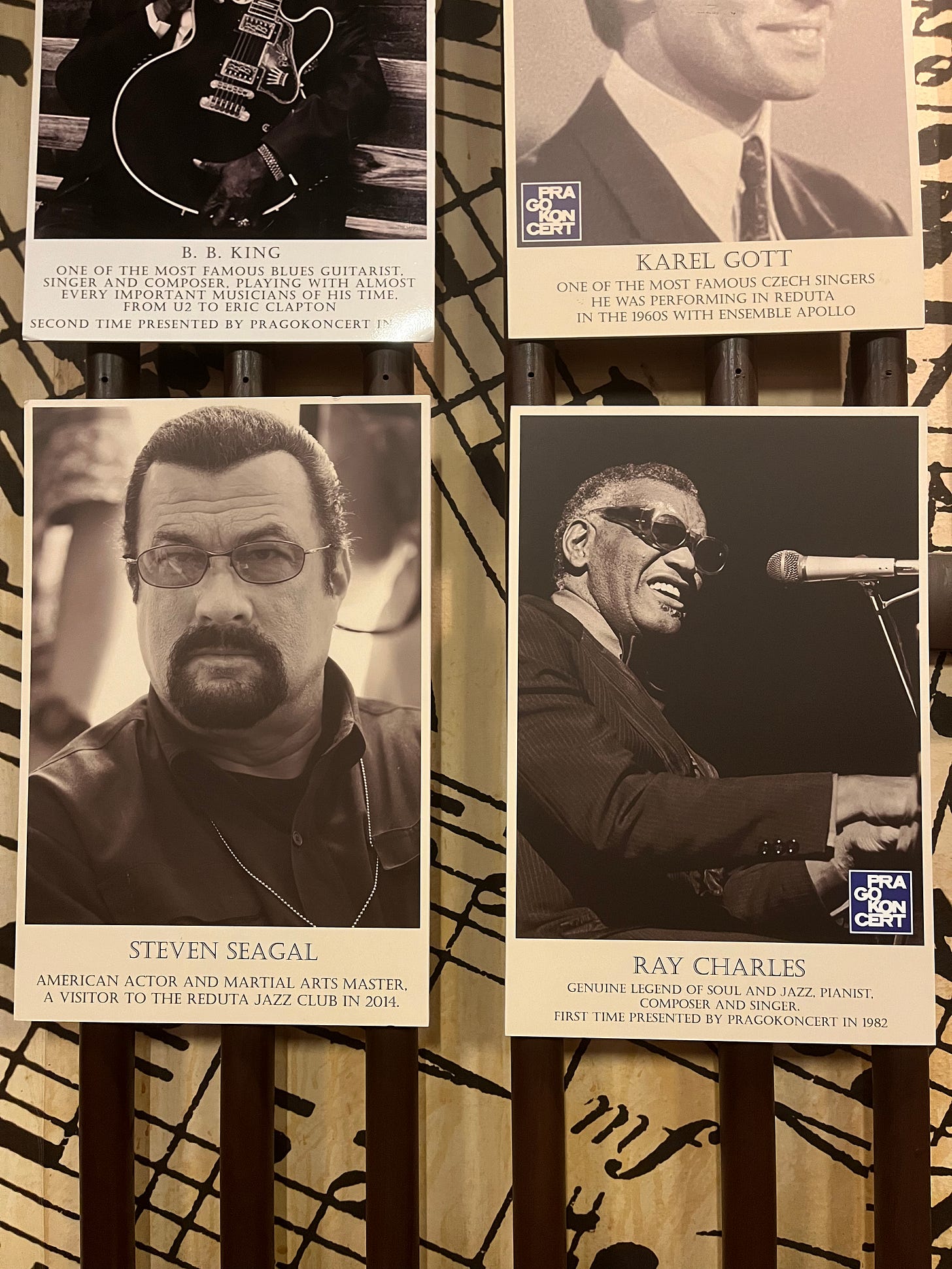

But to be clear, I knew what I was in for. Of course, we’re paying for the history here. The ticket was 395 CZK ($16.46 or 8.8 orange juices), far more than any other club ticket I’ve bought this summer. The walls are covered with photos of people who’ve played and visited this club. Oscar Peterson, Dave Brubeck, even Ella herself.

The singer asks in Czech how many Czechs are in the audience. One woman sheepishly raises her hand. I didn’t know quite what to make of it. I, an American, annoyed at other Americans for attending a show of Czech musicians playing a tribute act for an American in a Russian-owned club?

On one wall, Steven Seagal is next to Ray Charles. One of the photos above them has been removed, the adhesive residue left in the place of a portrait. But if Seagal is still hung up, who could have been removed? Pol Pot? Bernie Madoff? Sheryl Sandberg? When do we, as audiences, remove the portraits of our idols from the darkened velvet walls of our minds? When is our emotional adhesive too sticky? When do we, as society, drink the proverbial $1.87 orange juice in a foreign land, and when do we opt for a gin and tonic? Why are these metaphorical fake candles flickering in the musty clubs of our subconscious, and when do we blow them out by switching them off?

I asked the club manager what portrait had been there and why it was gone. “I don’t remember,” he said. “It fell down.” How dare he balk at my narrative.

I think Jazz in the Background exists for people who like to get things done. It appears as though someone has had too much jazz in the foreground.

Don’t suspend judgment. Judgment paves the way for good decisions.